Conserving the soil on new recycled landfill mining in The Netherlands

- Date2017-03-13 00:00

- View855

Conserving

the soil on new recycled landfill mining in The Netherlands

Ever since the European Union has

articulated a policy on landfill mining, member countries have been at the

forefront on how to conserve the soil based on or or newly recycled landfill mining.

Thus, The Netherlands clearly abides with

the European Union Directive framework on soil conservation from recycled

landfill mining. It has put forward a coherent policy on the conservation of

soil based on old or newly recycled landfill like cover material and fill

material. It has looked into a rationale that says Dutch environment will depend

heavily on policy developments in Europe and the rest of the world, that the

dependence on international environmental policy developments will also

increase, and finally that the economic interdependence of countries will also

rise.

Landfill mining and the European Union’s

regulation

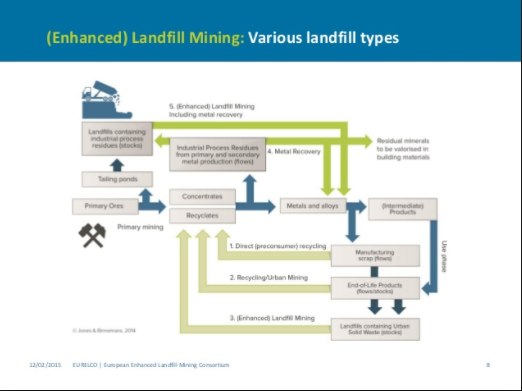

Landfill Mining (LFM) is a solid waste

management method which combines landfill engineering and mining techniques and

can be generally described as “a process for extracting materials or other

solid natural resources from waste materials that previously have been disposed

of by burying them in the ground.” (Robbinson, 2008). Historically, LFM was

first used in Israel in 1953 in order to produce soil for agricultural use. It

has become more popular in the late 1980’s when never landfills were applied

(Robbinson 2008: Ibid).

Different uses for LFM are established for

different uses: environmental policy and waste valorization opportunity and as

future possibility. An assessment of the current state-of play in Europe showed

that there is a lot of applied research needed in order to produce alternative

technological and financial models that could potentially support large-scale

LFM.

At the regional level, the

European Parliament and the Council of the European Union have established

major principles such as the obligation to handle wastes in a way that does not

have a negative impact on the environment or human health. This encourages to

apply the waste hierarchy and in accordance with the polluter pays principle, a

requirement that the costs of disposing of waste must be borne by the holder of

waste, by previous holders or by the producers of the of the product from which

the waste came (Cossu, et. al, 1996: 111). This is the first of all valid for

waste management in general but is to a significant extent applicable to

Enhanced Landfill Mining (ELFM).

When it comes to juridical

point of view, these complex policies can create serious implications for the

landfill mining projects. It can even pose a halt in a particular project.

However, according to the EU Directive, the mining must be carried without any

significant negative environmental disturbances on air soil and waters as well

as avoiding risks for the health of workers or people living in the

surroundings.

In

Europe, as a response to the EC Landfill Directive of 1999 and later the Waste

Directive of 2008, many landfills have been forced to close down during the

last decade. These directives have also led to the requirement that landfills

have a bottom liner. Likewise, it has also been stated that the landfilling of

organic waste must be phased out.

Nevertheless,

landfill mining is not so clearly regulated in the EU Directive and it has been

noted in the Directive 2008/98/EG that recycling of waste needs to assess the

existing definitions of recovery and disposal. This requires the need for a

generally applicable definition of recycling and a debate on the definition of

waste. The European Commission intended to clearly differentiate between

recovery and disposal and to clarify the distinction between waste and

non-waste. According to Cossu, et. al (1996: 115), clarifying these distinctions is particularly

important in the case of landfill mining.

Realizing

this the EU Council posits that:

“the first objective of any

waste policy should be to minimise the negative effects of the generation and

management of waste on human health and the environment. Waste policy should

also aim at reducing the use of resources, and favour the practical application

of the waste hierarchy. Hence, landfill mining needs to lead to a situation

where resources are used in a better way and old waste will have less effect on

the life of humans in coming generations.”

-EU Directive on Landfill

of Waste (1999)

The European

Council confirmed that waste prevention should be the first priority of waste

management, and that reuse and material recycling should be preferred to energy

recovery from waste, where and insofar as they are the best ecological options.

In the landfill mining concept it must first be decided if the recycling of

material is a realistic option compared to the energy utilisation alternative

(Ibid: 1999).

The EU

Directive means in practice that waste minimisation and pretreatment before

landfilling are encouraged and that this will result in ‘poorer’ landfills in

the future, possibly resulting in a lower interest in material recovery. After

the landfill has been definitively closed, the owner-operator shall be

responsible for its maintenance, monitoring and control procedures for 30

years, according to the Directive, or longer if required by the competent

authority. The costs are dependent on the expenditure and duration of the required

aftercare measures. (Johnson, 2008: 5.1)

Excavated soils and recovery of other

materials

The

waste status of uncontaminated excavated soils and other naturally occurring

material that are used on sites other than the one from which they were excavated

should be considered in accordance with the definition of waste and the

provisions on by-products or on the End of Waste status under this Directive.

It

is necessary to distinguish between the preliminary storage of waste pending

its collection, the collection of waste and the storage of waste pending

treatment. Establishments or undertakings that produce waste in the course of

their activities should not be regarded as engaged in waste management and

subject to authorization for the storage of their waste pending its collection.

Preliminary

storage of waste within the definition of collection is understood as a storage

activity, pending its collection in facilities where waste is unloaded in order

to permit its preparation for further transport for recovery or disposal

elsewhere. The distinction between preliminary storage of waste pending

collection and the storage of waste pending treatment should be made, in view

of the objective of this Directive, according to the type of waste, the size

and time period of storage and the objective of the collection. This

distinction should be made by the Member States. The storage of waste prior to

recovery for a period of three years or longer and the storage of waste prior

to disposal for a period of one year or longer is subject to Council Directive of

1999on the landfilling of waste. (EU Directive on Landfill of Waste, 1999).

Further,

the definitions of recovery and disposal need to be modified in order to ensure

a clear distinction between the two concepts, based on a genuine difference in

environmental impact through the substitution of natural resources in the

economy and recognizing the potential benefits to the environment and human

health of using waste as a resource. In addition, further guidelines or

implementing rules and regulations may be developed in order to clarify cases

where this distinction is difficult to apply in practice or where the

classification of the activity as recovery does not match the real

environmental impact of the operation.

Cost

and benefits for reclamation projects will vary considerably depending firstly

on the goal of the site owner-operator: reduction of the landfill area and cap;

recovery of airspace for continued operation; upgrading or installing a liner;

or removal of the landfill entirely or a combination of these. Secondly,

site-specific physical conditions play an important role in determining whether

the landfill operator’s goals can be achieved. These conditions include the

soil-to-waste ratio, depth of the waste, type of waste and the presence of

standing water, as well as costs for disposing of waste off-site if that should

be required(Johnson,

2008: 5.5).

Landfills

in The Netherlands from the 1960s, for example, have quantities of construction

and demolition waste materials, reflecting that era’s construction boom. Other

landfills include highly specific waste, such as that from vehicle

fragmentation companies. Increased environmental awareness and eco-trends have

favoured markets for recyclable and reusable material. Presumably the biggest

reason is the increase in the price of petroleum, which puts a new focus on

metal and plastic in landfills.

The future ahead of landfill mining and

solid waste and materials recovery

The

production of waste in EU has changed during the last decade as different types

of sorting schemeshave been introduced. The EU Council Directive of 1999 on

landfills has changed the landfill situation in Europe for the future. Scholars

have agreed that the EU Directive was intended to prevent or reduce the adverse

effects of the landfilling of waste on the environment, in particular on

surface water, ground water, soil, air and human health.

Many

earlier problems with landfilling will, to a great extent, be solved for future

projects, and that has motivated old landfill reclamation. No organic material

can go to landfills in the future. Further, they see the following three types

of landfills will exist in the future in the EU region: 1) inert, 2)

non-hazardous, and 3) hazardous landfills. There are hundreds of thousands of

old landfills in Europe and millions on the global scale. How many of these are

economically feasible to excavate and environmentally motivated to do today or

sometime in the future is difficult to say.

References:

Cossu, R., Hogland,

W. and Salerni, E., Landfill Mining in Europe and USA. ISWA Year - Book, International Solid Waste Association (ed),

pp. 107-114. (1996).

EU Directive on

Landfill of Waste. European Union Council Directive 1999/31/EC issued - 26

April 1999.

Johnson, M.,

Commercials prospects for landfill mining as part of a sustainable waste

treatment process, Proceedings of the Global Landfill Mining conference 9

October - 2008, Royal School of Arts, London,

UK, Page 5.1 -5.13 (2008)

Robinsson, G., 2008

Mining for plastics - Extracting plastics from landfills for materials

recycling and energy recovery. Proceedings of the Global Landfill Mining

Conference, 9 - October 2008, Royal

School of Arts, London, UK. Page 10.1 -10.10 (2008).

* Introduced here is an article written by one of KEI's environment correspondents. KEI invites students studying abroad and researchers working for foreign research institutes to send articles on various global environmental issues.

- PrevQuarry closed and exhausted mine recovery laws and cases: The European Union and The Netherlands Fra..

- NextPutting waste to resource: How the Dutch government transforms waste problem into solutions