The Dutch Policy in Reducing VOC Emissions

- Date2016-06-22 00:00

- View1,234

The

Dutch Policy in Reducing VOC Emissions

Lee Suk-Yeoung

& Chandradath Madho

Introduction

All nations of the world contribute to human-induced

emissions of VOC’s. However, the wealthier nations tend to expend large amounts

of energy and transport services. This culminates in high volumes of VOC

emissions which pose health risks to humans who may inhale noxious fumes. Also,

VOC emissions enhance the concentration of ozone in the earth’s lower

atmosphere. Hence, a few developed nations, like The Netherlands have

conscientiously pursued the agenda of a reduction in their VOC emission rates,

long before the Kyoto Protocol-1997 and the Rio Earth Summit-1992.

Dutch VOC-Reduction Policy

The

VOC-reduction policy in The Netherlands has been two-fold (Ministry of

Infrastructure and the Environment 2016). Firstly, there has been a concerted

effort by the State to improve local air quality via reduced ozone formations

and diminished benzene emissions The second strategy has involved limiting the

carbon footprint in the atmosphere, through the National Emission Ceiling criteria. The latter approach is less

based upon voluntarism and more etched in the imposition of sanctions upon specifically

targeted industries. Indeed, the emission ceiling has been executed in an

incremental manner since the 1980’s by integrating several stakeholders.

The

emission ceiling was imposed from as early as 1980 when the KWS2000 project policy was conceived,

and came into effect from 1988 (Sluijs, V. Risbey,J. and Ravetz, J.2005). This

plan ambitiously sought to achieve by 2001, a 50% decrease in the 1981 volume

of VOCs. In particular, paint coatings were considered a major source of

pollution. Rigid standards were therefore implemented to diminish the risk of

paint-based emissions. It must be appreciated that the State’s plan was also designed

in a way that incorporated the various 40 industrial sectors that were

notorious for polluting. These sectors were identified as being part of the following

industries: energy, road transport and industrial processing. Genuine attempts

were made by industrialists in oil refineries and in the chemical sector to

check their rate of VOC emissions.

Subsequent

to the year 2000 a more aggressive policy was pursued. The environmental goal

was revised via the National Non-Methane

Reduction Plan. This plan sought to procure an 80% reduction in VOC rates

in 2010, relative to the volume of VOC emissions generated in 1980. The

chartered ceiling of emissions was set at 185 CG.

It

was not long after 2010 that the Gothenburg

Proposal was revised in May 2012. This once again propelled the State to re-define

its target as an 8% reduction in VOC emissions, relative to the emission

volumes of 2005. The emission ceiling was therefore set at 158 CG. Interestingly, the Gothenburg Protocol was

drafted in 1999 as an EU directive within a larger framework on the Convention on Long Range Trans-boundary Air

Pollution which seeks to enhance aspects of environmental health. The fact

that the Dutch Government conforms to this protocol indicates that Netherlands

is drawn into an intricate regional agreement that obligates its employers and

citizens to act in a pro-environmental manner. For example, Dutch companies are

mandated by EU directives to comply with VOC-reducing techniques in order to

get their operating licenses to conduct business. These companies are also

monitored on an annual basis, to meet stringent environmental standards.

Failure to meet these criteria could result in the imposition of large fines.

Whilst

the national emission ceilings introduced in different decades generated

environmental compliance, other legal instruments were given salience by the

State. According to VROM (2002: 20): “Dutch Emission Guidelines, orders in

Council pursuant to Section 8.40 of the Environmental Management Act for

certain industrial sectors, environmental permit issues by Provinces and municipalities, emission standards for

transport traffic” have all been useful in reducing air pollution.

The

Dutch have sought to alleviate VOC emissions via an ongoing united approach

that encompasses various stakeholders: manufacturing industries, workplace

settings, households, and the transport sector. For example, all Dutch companies

are mandated to register for specific permits as part of an Activities Decree. If companies are

deemed to be involved in medium or high levels of combustion, they are expected

to be labelled as Type B and Type C companies respectively. Provision of

information to the State about levels of combustion of fossil fuels has been

mandatory, and crucial for the monitoring of emissions. This system has been in

place since 1992.

Meanwhile,

households and companies can also counter possibilities of VOC emissions by

restricting their usage of VOCs. This has been based on the Dutch ratification

of the EU VOC Product Directive. The

most significant example of the EU product Directive is based on the EU Paints

Directive of 2004. This dictate obligates paint manufacturers to clearly label

their paint solvents in terms of the lower and upper levels of acceptable VOC

percentage within the paint solvent and also, the percentage of VOC content

contained. Through product labelling, it is envisioned that consumers may make

an informed choice about regulating the VOC emissions.

Dutch

and EU products are being manufactured to reduce their likelihood of becoming

volatile. Whilst this a notable achievement, it is tough to impose sanctions on

non-EU merchandise. Hence, the general public is expected to be careful about

making purchases of foreign products. This requires a level of environmental

awareness by the Dutch public.

Outcomes of the Dutch

VOC Policy

In the initial period of the 1980s to 1999 the KWS 2000 Project achieved a 50%

reduction in VOC emission rates. This was especially laudable, since the start

of this intervention preceded the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 and EU environmental

legislation. Perhaps buoyed by the initial success, the VOC National Reduction Plan (excluding methane) in 2000 was more

aggressively pursued. It therefore resulted in a 34% reduction in VOC

emissions. In the current era of post- Gothenburg Protocol, the reduction

target of 158 CG by 2020 is projected to be attained because of the State’s

partnering with ships and oil-tank vessel companies.

The early decades of VOC-reduction did not

warrant compliance from the shipping sector. Whilst the energy companies and

manufacturing plants located on land-sites were being monitored, there was

little attention placed on auditing the pollution rates of ships. This

situation has now changed, as the logistic resources and personnel required for

monitoring and evaluation of Dutch VOC emissions have improved. This highlights

an evolution in the State’s capacity to mitigate against VOC-related pollution.

This State’s capacity has been buffered by the commitment of the EU agenda to

reduce VOC emissions.

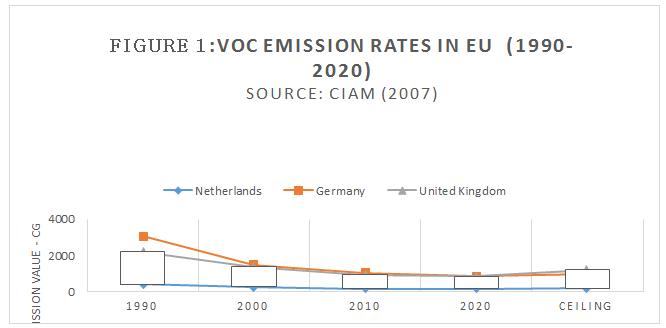

With reference to Figure 1 shown below,

Netherlands has managed to have lower emissions than rivalling manufacturing

giants like Germany and United Kingdom. All three countries have experienced

reductions in VOC emissions prior to the Gothenburg Protocol acceptance (CIAM

2007). This shows that genuine progress has been made by Netherlands and its EU

trading rivals in reducing VOC emissions.

It may be the case that the reduction in VOC

emissions is largely due to EU related policies that are generally directed at

industrial compliance to air emission protocols. For example, the 2010 Industrial Emissions Directive (IED)

20110/75 states that the nation-states like The Netherlands must be ready

to issue industrial permits in a manner that thoroughly checks on the general

ability of a company to reduce environmental pollution. Although a permit is

granted on a series of factors that includes the ability of a company to reduce

its VOC emissions among other factors, there is no denying the IED has created

pressure for industrial manufacturing plants to be more eco-friendly.

In attributing the success of VOC reductions

over the past three decades, Netherlands’ capacity to demand cooperation from

private companies has been crucial.

These companies have voluntarily demonstrated sound corporate

citizenship because they have accessed available technologies to reduce

emission; an operational cost that is incurred by these companies. It may not

be likely that developing countries or relatively poorer East-European EU

nations enjoy similar institutional strengths to diminish VOC emissions.

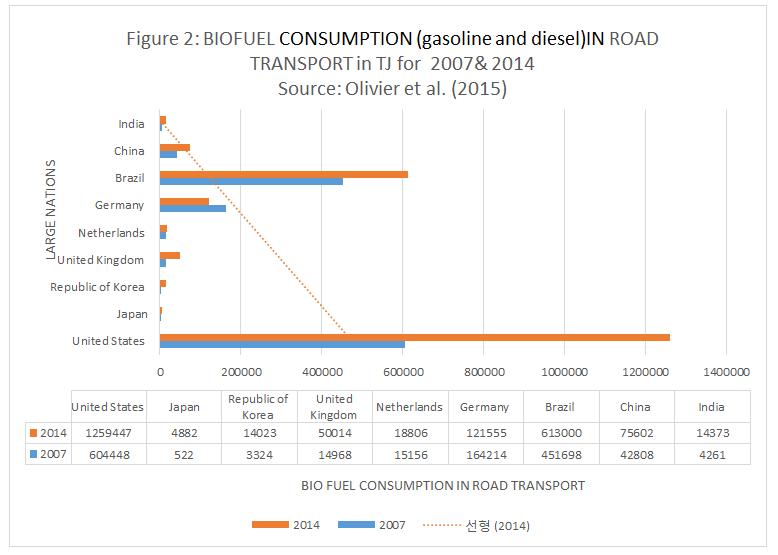

Additionally in explaining the success of the

Dutch model of VOC reduction it must be conceded that the State was not the

sole actor dictating the policy. International Conventions like the Kyoto

Protocol and the Copenhagen Climate Change Protocol may have applied subtle

forms of normative, global pressure, in order to locate VOC reduction within

the framework of sustainable development. This is evidenced in Netherlands’

reduction in biofuel (gasoline and diesel) consumption, which may showcase that

Dutch vehicle owners are becoming more environmentally aware of the usage of

bioethanol and biodiesel. As the Dutch use intra-city trams, inter-city trains

and cycling as modes of transport, it is not surprising that the Dutch are

outperforming European rivals in bio-fuel cut-backs. In fact the Dutch are also

performing better than large developed economies like the USA, and emerging

market economies like Brazil because these countries have larger populations

that leave a larger carbon footprint on the atmosphere. Although India seems to

consume less biofuel than The Netherlands, this statistic may be inaccurate or

unreliable, since measurement of consumption-statistics is often

under-estimated in developing countries. However, there is need to be cautious

about celebrating the Dutch reduction in VOC emissions, when compared to their

economic competitors.

[Source: Olivier et al 2015]

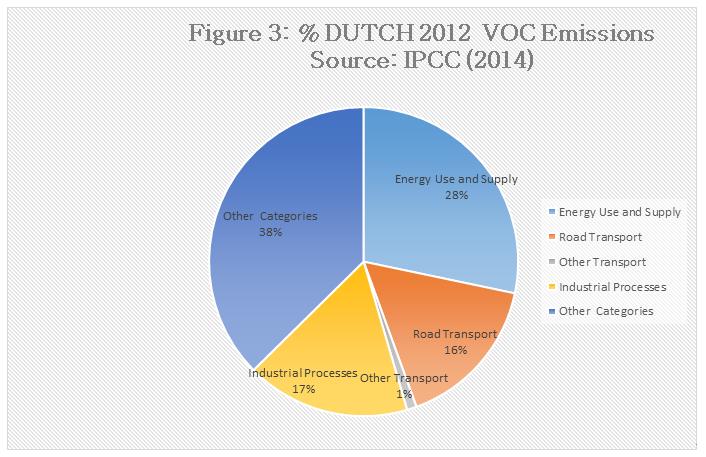

According to Figure 3 shown below, The

Netherlands has been polluting the atmosphere with VOC emissions via the Energy

Use & Transport Sector (28%) and the Road Transport Sector (16%). Even if motor-vehicle

bio-fuel consumption (gasoline and diesel) is lower than other countries, the

Dutch policies about reducing VOC emissions must not be relaxed. This means

that Netherlands must continue to find solutions to downsize their carbon

footprint.

[Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2014]

Suggestions about

further reductions in VOC emissions

The road- transport sector’s contribution to

pollution could be further reduced if incentives were given to encourage a

higher use of trams and trains by civilians. Such a plan will stimulate a

reduced usage of cars. However, the public transport services are currently

very expensive, and may repel citizens from reliance upon these services. The

Government should therefore seek to provide a tax break as an incentive to public

transport companies that reduce the fares for the use of trams and trains.

Another way of countering VOC emissions is to

encourage the teaching of environmental studies within the public school’s

curriculum. By infusing relevant life-long lessons about the sources of VOC

compounds and their associated dangers, there is a great likelihood that children

would transmit this information to families. Also, the Government needs to

engage with the mass media and social media more proactively, to warn citizens

and workplaces about the risks associated with using paint solvents in

particular and also about the benzene content contained in cigarette smoke.

CONCLUSION

In general, The Netherlands has successfully reduced

VOCs due to the confluence of EU regulations, international conventions and

Dutch indigenous policy making. This united

agenda must continue if greater strides are to be made. In the aftermath of the

2015 Paris Climate Convention, The Netherlands should be encouraged to provide

technical assistance to developing and rich nations, regarding monitoring and

regulation of VOCs.

References

[1] British Broadcasting

Company (BBC) (2015) ‘Netherlands ordered to cut greenhouse gas emissions’ 24

June 2015 Issue. Accessed 26 May 2016 < http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-33253772>.

[2] Centre for Integrated

Assessment Modelling (CIAM) (2007) Review

of the Gothenburg Protocol. Bilthoven: Netherlands Environmental Agency.

Accessed May 26 2016 <www.emep.int/publ/other/TFIAM_ReviewGothenburgProtocol.pdf>.

[3] European

Commission (2010) The Industrial

Emissions Directive 2010/75/EU. Accessed 26 May 2016 < http://ec.europa.eu/environment/industry/stationary/ied/implementation.htm>.

[4] European

Environment Agency (EEA) (2016) Air

Pollution Fact Sheets 2014. Copenhagen: European Environmental Agency.

Accessed 26 May 2016 <http://www.eea.europa.eu/downloads/d838969a52594e3d919437113e98b626/1458048360/air-pollution-country-fact-sheets-2014.pdf.>

[5] Goldstein, A.,

Galbally, I.E. (2007) ‘Known and Unexplored Organic Constituents in the Earth's

Atmosphere’, Environmental Science &

Technology: 41(5):1514?21. 17396635.

[6] Intergovernmental

panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014) Climate

Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to

the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Accessed 26 May 2016 <https://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/tar/wg1/140.htm>.

[7] Keller, M., &

Lerdau, M. (1999) ‘Isoprene emission from tropical forest canopy leaves’,Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 13(1): 19-29.

[8] Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening

en Milieubeheer (VROM)(2002) Emission ceiling acidification and

continental air pollution report of the Netherlands. Accessed 26 May 2015 <http://ec.europa.eu/environment/archives/air/pdf/200181_progr_nl.pdf>.

[9] Ministry of

Infrastructure and the Environment, Government of the Netherlands (2016)

Volatile Organic Compounds. Accessed on 24 May <http://rwsenvironment.eu/subjects/air/volatile-organic/>.

[10] Olivier, J.

Jenssens-Maenhout, G., Muntean, M. and Peters J. (2015) Trends in Global Emissions. The Hague: PBL Netherlands Environmental Agency. Accessed

26 May 2016<http://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/cms/publicaties/pbl-2015-trends-in-global-co2-emisions_2015-report_01803.pdf>.

[11] Van Der Sluijs, J.

P., Risbey, J. S., & Ravetz, J (2005) ‘Uncertainty assessment of VOC

emissions from paint in the Netherlands using the NUSAP system’, Environmental

monitoring and assessment 105 (1-3): 229-259.

* Introduced here is an

article written by one of KEI's environment correspondents. KEI invites

students studying abroad and researchers working for foreign research

institutes to send articles on various global environmental issues.

- PrevThe Dutch Environmental Welfare System

- Next[Climate Change] Adoption of the Paris Agreement by the Conference of the Parties (COP) - December 2..